In my last post I reviewed the five stages of grief as outlined by Elizabeth Kubler Ross in her book “On Death and Dying. As I pointed out, while the stages of grief and loss were originally introduced to help people understand reactions to death, these stages are equally applicable to other forms of loss that may occur. In this post, I will focus specifically on the form of trauma and loss with which I am all too often asked to assist, that of infidelity in relationships.

What is (In)Fidelity?

The meaning of the word fidelity may be debated with regard to the line between acceptable and unacceptable behavior in relationships, but strictly speaking, fidelity is defined as “strict observance of promises and duties, loyalty, conjugal faithfulness, adherence to fact or detail, and accuracy or exactness.” As this definition shows, fidelity is multifaceted. Many times, disagreements and conflicts over fidelity within relationships are based on different values with regard to any one or more of these facets. However, typically when we refer to infidelity, we are referring to sexual or romantic interaction outside the bounds of the marriage or relationship to which one is expected to be committed.

Infidelity has existed as long as values that promote fidelity have existed. It is not a new issue, nor is it a temporary issue, reserved for our particular zeitgeist in history. It is not unique to our culture or society or era. However, due to the rapid increase in ability and opportunity to connect with other people, especially as afforded by social networking, opportunities for infidelity are more commonplace and available than they ever have been in recorded history. Combine that availability with a culture that is geared towards instant gratification and the delusional belief that the individual is more important than the collective that you have a perfect storm.

Infidelity in relationships may occur in the form of inappropriate text messages, e-mails, Facebook or Twitter messages, workplace friendships, along with the more traditional haunts. Many individuals consider the use of pornography by their partners to be a form of infidelity. In addition to the variety of avenues through which people may be unfaithful to each other, there is also a multidimensional spectrum within which any avenue of infidelity may be found. The two most important dimensions with regard to infidelity are the degree of physical involvement and the degree of emotional involvement. When viewed multidimensionally, it is easy to see that not all infidelity is the same. One person may impulsively kiss a coworker after having had too much to drink at the Christmas party. Another person may actively pursue a romantic relationship with their next-door neighbor, one that is initially built on common interests and proceeds to common complaints about their respective partners. It is not for me to say which of these two forms of infidelity is worse or more painful than the other; that is for each affected individual to determine.

However, despite the multitude of avenues and multidimensional aspects of infidelity, once it has been discovered or revealed, the partner of the person who has acted in such a way will usually respond within a certain range of expected behaviors and feelings. The purpose of this post is to briefly outline what those expected behaviors and feelings may be. The usefulness of describing these stages is so that people who are somewhere along the path from trauma to recovery will be able to see that their experience is not unique to them, that they do not suffer alone, and that there is a predictable outcome to their suffering.

Five Stages of Grief After Infidelity

Denial

The most common way that denial appears after infidelity is what I call premature optimism. After the initial shock of discovery or revelation, the partner may effectively go numb. This will lead to them appearing as if they are relatively unfazed by what has happened. They may speak optimistically about their hopes of reconciliation, of seeking professional help to make their relationship work, or of their forgiveness and understanding for what has happened. They may also “talk tough” about how the relationship is over and generally try to appear like they are ready to move on. While sometimes this optimism is genuine and appropriate, often, it is premature in that it is not based on a sound understanding of what has transpired, its true emotional impact, and its ramifications for the future. The benefit of this stage is that by rushing to focus on solutions, the injured partner is able to avoid painful feelings and make it through the day.

The most common way that denial appears after infidelity is what I call premature optimism. After the initial shock of discovery or revelation, the partner may effectively go numb. This will lead to them appearing as if they are relatively unfazed by what has happened. They may speak optimistically about their hopes of reconciliation, of seeking professional help to make their relationship work, or of their forgiveness and understanding for what has happened. They may also “talk tough” about how the relationship is over and generally try to appear like they are ready to move on. While sometimes this optimism is genuine and appropriate, often, it is premature in that it is not based on a sound understanding of what has transpired, its true emotional impact, and its ramifications for the future. The benefit of this stage is that by rushing to focus on solutions, the injured partner is able to avoid painful feelings and make it through the day.

This is a very subtle form of denial. In some cases the denial is much more flagrant. In these cases, the injured party may simply shrug their shoulders and assume that there is nothing that they can do, saying that it is in the past and that the only thing to do is move on and let it go. The most flagrant form of denial, obviously, is the actual denial that anything is going on or has gone on. Making excuses for the offender, finding alternate explanations for what is clear to all objective observers, or saying “I don’t want to know”, all serve the same purpose as more subtle forms of denial: to prevent painful emotions. As we will see throughout this list, the first three stages of grief preceding the fourth stage, mourning, serve that same purpose.

Bargaining

Kubler-Ross originally included this stage as preparatory to death or dying and in that context, it makes more intuitive sense that someone would try to bargain to avoid a fate they would rather avoid. However, when the loss has already occurred, bargaining doesn’t seem to be a natural fit. After all, we can’t go back in time to make something unhappen. So how could we bargain in this stage?

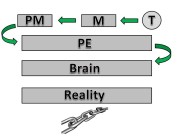

Simply put, the bargaining stage entails a lot of 20/20 hindsight coupled with self-blame. “If I only I had done this or seen that…” “How could I not see this coming? Where did I go wrong? What did I do wrong?” “If only …” “I should have…”, “They should have …” All of these statements are an expression of a universal desire to change undesirable circumstances after the fact. However, as stated above, we cannot do this. What we can do, however, is imagine ourselves acting differently and as far as the brain is concerned, this is the next best thing.

As I have touched upon with numerous other posts, the brain cannot easily tell the difference between what I am imagining and what has actually occurred. The bargaining stage of post-traumatic grief is an unconscious attempt to inhabit a different reality that the one we are confronted with. Denial serves this same end but at a greater distance from the pain. The bargaining stage acknowledges that things are not good but attempts to live in an imaginary world where things have worked out better. Keep in mind, as we move through these stages, that they are logical responses to pain, not stupidity.

As I have touched upon with numerous other posts, the brain cannot easily tell the difference between what I am imagining and what has actually occurred. The bargaining stage of post-traumatic grief is an unconscious attempt to inhabit a different reality that the one we are confronted with. Denial serves this same end but at a greater distance from the pain. The bargaining stage acknowledges that things are not good but attempts to live in an imaginary world where things have worked out better. Keep in mind, as we move through these stages, that they are logical responses to pain, not stupidity.

Anger

The anger stage after infidelity is easily recognized. Anger may be directed at the offending partner, the third party, or even at oneself, as covered in the bargaining stage. However, while anger is recognizable and understandable as a response to infidelity, it is not immediately apparent that this anger is actually part of the grieving process. Generally we associate grieving with sadness but as we have seen thus far, it is a bit more complex than that. Adding to that complexity is when the relationship was rocky prior to the infidelity. This often means that the infidelity was A) not entirely unexpected, B) may offer a way out of a relationship, C) is still hurtful, D) may remove the veil of denial from the state of the relationship, E) may be a relief… etc.

The anger stage after infidelity is easily recognized. Anger may be directed at the offending partner, the third party, or even at oneself, as covered in the bargaining stage. However, while anger is recognizable and understandable as a response to infidelity, it is not immediately apparent that this anger is actually part of the grieving process. Generally we associate grieving with sadness but as we have seen thus far, it is a bit more complex than that. Adding to that complexity is when the relationship was rocky prior to the infidelity. This often means that the infidelity was A) not entirely unexpected, B) may offer a way out of a relationship, C) is still hurtful, D) may remove the veil of denial from the state of the relationship, E) may be a relief… etc.

The anger stage of grieving also gives the traumatized partner the strength and energy to face the logistical challenges that present themselves if a separation results. This may include becoming a single parent, a single breadwinner, continuing in essential routines connected to both roles, etc. However, while there was an initial survival benefit of this response, it is also important to recognize that the benefit wanes over time.

Another key component of this stage is the realization that anger is fear, at its roots. It is simply one side of the fight or flight response. No matter which way we follow, the underlying message of the brain is the same: You are in danger and your defenses must be mobilized. Reinterpreting anger as fear will allow us to get to the bottom of the issue faster instead of getting waylayed in draining resentments. Asking ourselves the question, “What am I afraid of?” will also serve as a catalyst for moving into the next stage of grief in particular.

Mourning

This stage of grief has been referred to as mourning but Kubler-Ross originally called it “depression”. There is a critical difference between these two terms, albeit a subtle one that is usually lost on people who have not experienced depression. The difference is that the fuel behind depression is hopelessness. It is one thing to be sad that something happened and quite another to feel as if things will never be better, that there is no hope for improvement, and only a destiny of doom awaits.

This stage of grief has been referred to as mourning but Kubler-Ross originally called it “depression”. There is a critical difference between these two terms, albeit a subtle one that is usually lost on people who have not experienced depression. The difference is that the fuel behind depression is hopelessness. It is one thing to be sad that something happened and quite another to feel as if things will never be better, that there is no hope for improvement, and only a destiny of doom awaits.

With regard to infidelity and this stage of grieving, the feelings are usually along the lines of “I can never trust him/her again” or “I can’t trust anyone” or “I’ll never be able to forget and move past this”. These are absolute, concrete, black and white statements, obviously, and project a future that is based on the present. We know that past behavior can be an accurate predictor of future behavior but this is not absolutely true. It is true to say that right now, trust seems impossible but it is not necessarily true that it will remain so forever. If people work through their issues, learn to communicate better, learn how and who to trust, then trust can once again become a part of their life. If nothing changes, however, then nothing changes.

When someone is in this stage of grief, reassurance will have very little effect. Telling someone that one day they will be able to trust again when they are in the throes of betrayal is like telling someone who is freezing to death that it’s not really that cold. Having said that, for them to recognize that these feelings are a natural response to what has happened, that many people have gone down this road and come to this exact spot but eventually moved past it, is crucial to progressing to the final stage. We allow someone to make this progress when we do not pressure them to get there faster. We cannot rush trust.

You will notice that what is being grieved in this stage is not necessarily the loss of the person or even the relationship, but the loss of an ideal. It is disturbing to think that my partner has betrayed my trust but much more disconcerting to realize the reality that partners sometimes betray trust. If the assumption of loyalty and fidelity formed a foundation of my expectations of relationships in my life and that foundation has now crumbled, we have lost much more than one particular relationship; we have lost trust in our own expectations.

Acceptance

Referring to this stage as the final stage may be somewhat misleading. It gives the impression that once we have progressed to acceptance, the other stages are over and done with. If only that were true. However, once we have resolved this stage, it does make it much easier to handle regression into earlier stages and also allows us to recover from those regressions faster. By coming to some acceptance of what has happened, it gives a different context in which to deny, bargain, get angry, and mourn.So what do we mean by acceptance?

Referring to this stage as the final stage may be somewhat misleading. It gives the impression that once we have progressed to acceptance, the other stages are over and done with. If only that were true. However, once we have resolved this stage, it does make it much easier to handle regression into earlier stages and also allows us to recover from those regressions faster. By coming to some acceptance of what has happened, it gives a different context in which to deny, bargain, get angry, and mourn.So what do we mean by acceptance?

In my last post, I described it like this

“This is not to be confused with the idea that they are happy about the loss or even that they no longer resent the loss. It simply means that they are completely aware of the loss, that there is no more denial, no more blame, no more “what if…” and no more hopelessness.”

Coming to a place of acceptance with infidelity does not in any way indicate that we condone the behavior, that we are not hurt by it or that it doesn’t affect us. It certainly doesn’t mean that we are happy about it and tolerant of it. It means that we have stopped trying to avoid the truth and are working on putting it into perspective.

With regard to infidelity, acceptance may involve accepting that you no longer trust your partner and for good reason. It may involve accepting that you now want to “snoop” and look for evidence of recurrence. So many of my clients battle this part of the process by saying that they don’t want to become “that guy” or “that girl” who is always suspicious and checking on their partner. In response to that, I tell them that whether they want it or not, that is exactly who they have become and that it is OK. This is normal, predictable, and even healthy behavior following a betrayal.

With regard to infidelity, acceptance may involve accepting that you no longer trust your partner and for good reason. It may involve accepting that you now want to “snoop” and look for evidence of recurrence. So many of my clients battle this part of the process by saying that they don’t want to become “that guy” or “that girl” who is always suspicious and checking on their partner. In response to that, I tell them that whether they want it or not, that is exactly who they have become and that it is OK. This is normal, predictable, and even healthy behavior following a betrayal.

One of the reasons we have a difficult time accepting this evolution in ourselves is because we struggle to see what has happened as a trauma. But, if we can recognize it as such, it will give us the proper perspective to understand our responses and have compassion for ourselves. If you were in a traffic accident where someone ran a red light and caused you serious physical harm, no one would begrudge you for having anxiety the next time (or the next 300 times) that you got into a car and drove through an intersection. It is an understandable artifact of what happened to you. Why should it be any different with trusting your partner? How can we begrudge a person for being overly cautious with their trust when it was already betrayed (perhaps more than once)?

Acceptance may mean terminating the relationship. Not all relationships are salvageable, particularly if only one of the parties is interested in making changes. Acceptance may mean recognizing our own contributions to the situation while still holding our partner accountable. Ultimately, acceptance is about incorporating what has happened into our lives without letting it define our lives from here on out.

A couple of years ago, I was laying on my bed, full of frustration at myself, or more specifically, at my ADHD. It was driving me crazy. I lay there beating myself up, cursing God for cursing me, wishing that I could just be more organized, focused, at peace, etc. I felt these feelings consuming me. Then, a window opened in my mind. I realized that my ADHD was not going away. It is not a “curable condition”. It can only be understood and managed. I realized that every day I spent hoping that the ADHD would be gone could only end in disappointment because, simply, it was not going away. I realized that I would just have to accept that that was how my brain worked, be content with managing it, learning to manage it better, and focus on some of the positives. I’d like to be able to say that that moment of insight was enough to rewire 35 years of brain development but it wasn’t. It did, however, start a new direction of development. From time to time, I still get frustrated with the way my brain works and return to my list of complaints and resentments. However, due to the window of acceptance that was opened in my life, it is much easier for me to return to gratitude and determination, knowing that I am not my ADHD. It is a part of me that is not going away but it doesn’t have to dominate and define me.

From acceptance, we can move into a new realm of post-traumatic experience, referred to as post-traumatic growth. This allows us to find purpose in our pain and ultimately, to heal. I hope that in reviewing these stages, you have learned something, realized something, remembered something, or at the very least, understood yourself better.

From acceptance, we can move into a new realm of post-traumatic experience, referred to as post-traumatic growth. This allows us to find purpose in our pain and ultimately, to heal. I hope that in reviewing these stages, you have learned something, realized something, remembered something, or at the very least, understood yourself better.

If you liked what you read, want to know more, or have any questions, please feel free to contact me at ted@connectivitycounselling.com

[…] greiving infidelity in relationships – Connectivity Counselling http://connectivitycounselling.com/what to expect after romantic or sexual infidelity. mourning, grieving, cheating, crying, sex, all mixed together. […]

Thanks for writing this – it makes so much sense, especially how you described bargaining in the infidelity sense rather than in the death grief sense, and I find it a little amusing that I went through these stages with clockwork precision. I’m stuck between depression and acceptance. I forgive – of course I did it right away when he told me – but now I really do, and am trying to live in this new reality where I believe our marriage to be worth fighting for. I won’t give up, but this literal pain in my heart and stomach seems permanent, and I’m praying each day for it to get better. I don’t know what else to do.

Thanks,

Beth

How are you now? Has the pain in your stomach and heart eased? I’m right at the start and it’s killing me.

Thank you for this. I am on day 2 of the process – I just found out about my husband’s affair. I guess I am numb now – can’t wait for the bomb to drop!

Besides the infidelity i am also grieving for my non existent pregnancy we planned

sorry to hear that. As the article mentions, the implications of the loss, the ripple effect, is often what keeps the pain going.

This article was highly helpful. My husband had an emotional affair and told me he was in love with her, yet sorry. Had I known that I would experience post traumatic stress disorder from finding this out, would have helped me feel like I wasnt going crazy. And now that I’m slowly getting out of that phase, I realize now that I’m going through stages of grief.

Our relationship has been damaged severely. I feel like I don’t know him. Don’t trust him and feel I never will.

Hearing about these stages is giving me relief from rushing my own healing.

Thank you for writing it, Ted, it was highly helpful.

Thank you for writing this… It truly has helped me to be more compassionate with myself, I found out about my husbands affair with a co-worker a year ago, and I had been truly struggling to accept that yes I do need to snoop from time to time, yes I don’t know if I will trust him again right now, and that yes I am grieving for the ideal of relationship I thought I had… and that is OK… And also that getting to one stage doesn’t mean the process is over, I can regress to other stages and that is OK to!! This is my second marriage (my ex husband also cheated on me), and I truly believed this would not happen again to me, so I guess the trauma is even harder, and I must be patient with myself…. It makes a lot more sense after reading your post… I will keep coming back to read it when the need arises… Thank you…

I just don’t know what stage I am in anymore. I fluctuate between anger and depression. I too mourn for the children I never had bc he told me he NEVER wanted children. Now he’s remarried to a young woman and has a baby. It’s too late for me to have children now. That is what depresses me and makes me angry. I get angry at anyone who doesn’t feel my pain and tells me to move on. It’s been 8 years and I still love him. Besides killing myself, I feel like there is no light at the end of this dark tunnel.

How are you doing now? I’m sorry you’ve had to go through this.

Leslie, consider adopting. Thousands of children need your love and support. Consider the universe have a different plan and need for you. There is one or two children who suffer out there. Your love will heal you both. Also there are tons of loving men too. Hang in there. It will pass. Open up to possibilities.

Great article. I like your analogies.

Thank you for writing this. I’m a week into this after finding out of my fiancee’s affair with a woman on his pool team. Ive visited and revisited these stages, as he did not come clean to me with the details I needed and, when I tracked them down on my own, the stages restarted all over again. After reading the stages, I’m bouncing between mourning, anger, and bargaining. He says he’s ended things with the other woman and wants to stay with me and our two young children (7 months and 13 months) and that the affair had nothing to do with me (our sex life never took a dip and was always fantastic) and that he loves me. After seeing the text conversations with this woman I cant believe he didnt have feelings for her, though he swears he doesnt – that it was all “just talk”. I feel like I’m drowning. I still love him, oddly enough, and am desperate for this to have never happened and to feel certain for it to never happen again. I know I can never be sure – I’m struggling with trust. I feel so hopeless in all of this and I dont know how to move on from it to repair our relationship. He seems to be trying to help me through things, but I’m now cynical that he even cares. But why would he stay if he didnt? I dont know anymore.

Am a week old after finding out that my wife was cheating on me with another married man whom she met in college. I don’t know which stage am in and don’t even know why she did it. After reading this blog am beginning to understand that am not being stupid but am passing through the normal stages of pain. We are still together because I still love her so much and because of the two kids we have together. Still hoping this pain wiĺl go away one day & that we will continue being husband and wife.