Ok, it’s been 10 days since I finished writing the first installment of this article. I kind of knew that would happen. I knew it would happen because it’s happened so many times before. Despite this knowledge, I often feel powerless to do anything about it. Today, I’m going to address another reason why I might feel that way as well as making some suggestions that might help to overcome it.

Lack of Motivation

This may seem overly obvious as an explanation but motivation is much more biological (biochemical, to be specific) in nature than people realize. Wanting to do something isn’t as simple as being interested in doing it and then doing it. In order for any activity to be motivating, even those that we experience as intrinsically rewarding or intensely pleasurable, we rely on the presence of a critical neurochemical known as dopamine. Dopamine has many functions, depending on where in the brain and body it is being used. It is a pleasure chemical (stimulants increase dopamine levels, as does sexual activity). It also provides physical energy. It is implicated in control of fine and gross motor control (Parkinson’s patients don’t have enough dopamine in the part of the brain that controls movement). Because of the pleasure and energy that it provides, it also plays a vital role in motivating people (and animals) into action. Simply put, dopamine is the gasoline that makes the motivation engine run (or the electricity if you drive a Nissan Leaf).

Is that a car, or a pet?

Because the release and absorption of dopamine is rewarding, activities that produce an increase in dopamine will be desirable for the brain to engage in and repeat. As mentioned before, even the most basic drives are often mediated by dopamine. Sex is enjoyable because it increases dopamine (among other brain chemicals). Drugs are enjoyable (initially) because they increase dopamine. Eating cake is enjoyable because it increases dopamine. Studies with animals demonstrate that chemically or surgically altering the brain so that dopamine is no longer produced or absorbed will result in the animal discontinuing activities that it previously enjoyed or appeared to participate in instinctively (such as sexual activity or grooming behavior from parents to children).

Mmmm. With delicious dopamine frosting. and filling.

What does this have to do with procrastination? If the task that I am supposed to complete does not cause a sufficient release of dopamine in response, my brain will naturally struggle to recruit the internal resources required to follow through on the task. Some activities naturally produce more dopamine than others but there are also idiosyncratic activities that appeal more to one person than another. When we say that taste is subjective, what we are really saying is that certain things produce more dopamine for some than for others. Not everyone experiences a rush of dopamine release when reading comic books but some certainly do. Not everyone experiences a rush of dopamine at the thought of jumping out of an airplane, but some certainly do. Sometimes this dopamine release is due to past experiences and exposure and sometimes it pre-exists. We’re not really sure why, but some people are just naturally predisposed to love Pokemon and some aren’t.

I’m not sure how evolution would naturally select this mutation.

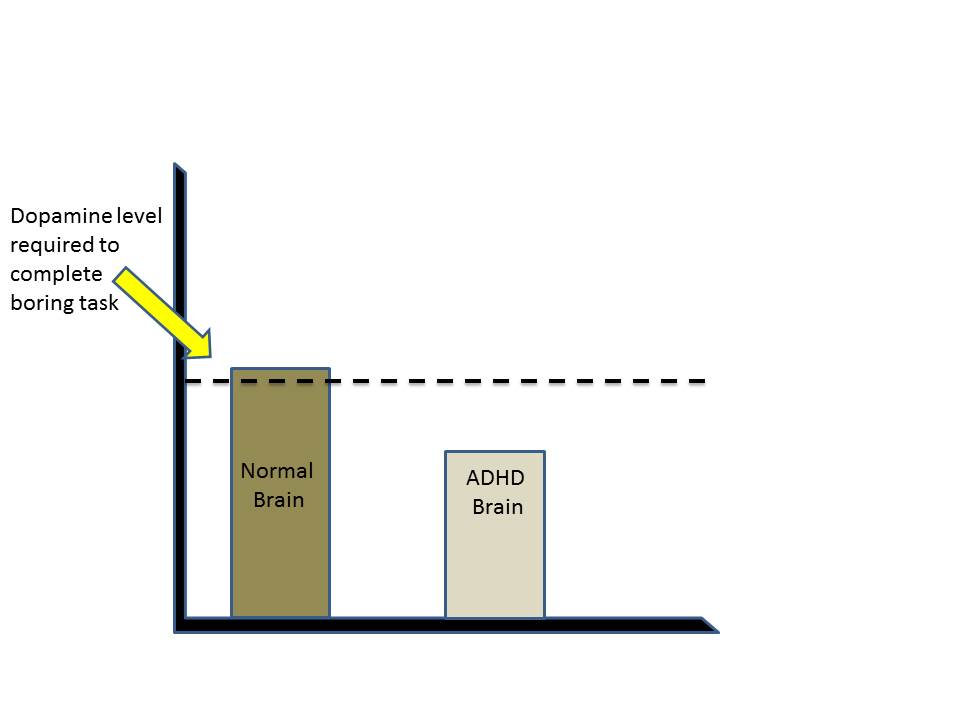

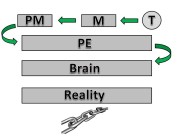

As with working memory, folks with ADHD (the world champs of procrastination) appear to have a naturally low level of dopamine in the brain areas involved in motivation. This means that activities that regular people struggle to get motivated for, such as cleaning the bathtub or writing boring essays for school, are extremely undesirable for the ADHD brain. Perhaps this makes more sense visually.

If the gas tank of your car is empty, you can’t “will” it forward. It just won’t go. For the ADHD brain, in terms of motivation for uninteresting tasks, it is simply running on fumes.

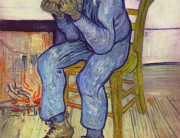

Although it could be its own installment (I’m actually working on that one at the same time as this one), there is an idea related to motivation that is often involved in procrastination. This is known as learned helplessness. Learned helplessness refers to the tendency to give up when things get difficult or, more importantly, to not even begin a task or activity because of the belief that it will inevitably be unsuccessful. From my experience, this learned behavior is much more likely to be found in people with ADHD, although it is certainly not exclusive to that group. In order for a task to be motivating, (i.e. produce an increase in dopamine), it needs to have been a positive experience. For many people, having an assigned task is only associated with failure, embarrassment, or underachievement. Their brain has learned that falling on your face is more likely than leaping tall buildings. As such, the mental image associated with the task is a negative one. It is not likely that picturing a negative event, either from the past or from an imagined future, will result in an increase in dopamine. As we know, if there is no increase in dopamine, there is no motivation.

I believe that, for myself, this is a chief cause of much of my procrastination, including the completion of this article. My brain, when faced with the prospect of following through, simply says, “Hey, based on past experiences, you probably won’t finish this. Therefore, let’s be more efficient with our energy and not waste it on starting in the first place.” Even as I complete the first section, my brain revolts against the progress, arguing, “Don’t bother starting the next one. You won’t finish it. You rarely do. Save your energy”. In many cases, the brain presents a compelling argument. I have, in fact, often left projects half-finished (or even more maddeningly, 95% finished). Based on this track record, could my brain be right? Would it be more efficient to not bother? I’ll address this in the next section.

What to do?

I think Walt Disney was really onto something when he, through the lovely Mary Poppins, reminded us that a spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down. In fact, one of my favourite breakfasts to this day is cold oatmeal. Just oats in a bowl with milk. And sugar. I asked my mom one time how she convinced us to eat this when we were little kids, as it doesn’t look or sound very appetizing. She said, “Kids will eat anything if you put enough sugar on it”. True indeed.

Um, we’re gonna need a lot more sugar over here!!

What does this have to do with motivation? Well, simply stated, pairing activities that naturally increase dopamine with activities that don’t is a good way to piggyback the motivation from the first activity onto the latter activity. In other words, if loading the dishwasher doesn’t naturally produce an increase of dopamine, but listening to Justin Bieber bust some rhymes does, then listen to the Beebs while loading the dishwasher. The dopamine from the desirable activity will carry over to the undesirable activity, resulting in increased energy to get the job done.

um… I’m not sure what this picture says about our society but I don’t think it’s anything good

This isn’t always possible, but it’s often more possible than we realize. Often, teachers and parents will set up reward programs where 60 minutes of work equals 15 minutes of screen time or fun time. In theory, the dopamine increase from the potentially rewarding activity should drive the person to complete the less desirable activity in order to obtain the reward. In practicality though, it often just makes the undesirable activity that much more undesirable. Think of the day before a big, much anticipated event. Often the day just seems to drag on, taking forever, and leading to double checking the time to make sure that the clock hasn’t stopped. The contrast between the desired activity and the undesired activity can be amplified by using the desired activity as a carrot on a stick. I think it is more useful to pair the desired activity with the undesired activity simultaneously whenever possible. This might mean listening to music, or reading or while walking on a treadmill, or making learning fit into the student’s naturally rewarding activity as much as possible. Kids who love video games and hate math will love math-based video games.

These kids are LOVING long division!!

The other facet that needs to be approached is the nature of learned helplessness. Of course, the brain’s desire to be efficient in its use of energy has led to its conclusion that making effort in areas that will inevitably lead to failure is a waste of resources. According to the brain’s logic, this makes perfect sense.

1. If resources are scarce, then only use resources on tasks that are guaranteed to be successful.

2. Engaging in this task is not guaranteed to be successful,

3. Don’t waste resources on it.

It’s perfectly logical. However, there are some flaws when it comes to the accuracy of these premises.

1. Resources aren’t that scarce.

2. Success can be defined in many different ways, not all of which are tied to the eventual outcome of a task. To have tried and fall short is arguably more successful than to have never tried at all. Surely some learning or some accomplishment is better than no accomplishment at all.

3. Just as there is no guarantee that the task will be successful, there is no guarantee that it won’t be successful.

As I have said previously, there is much more to be said about learned helplessness, so I will leave that topic for later (no really, I’m going to come back to it. I promise).

So if the reason for your procrastination is a combination of lack of motivation, try to pair the undesirable, boring, or painful task with something that you value or enjoy and see if the dopamine from the latter will help to ease the pain of the former. I’m interested in your feedback, so feel free to leave a comment below or send me a message.

Recent Comments