Fight, Flight and … Freeze?

Most people have heard of the “fight or flight” response. It is the body’s naturally hard-wired way of dealing with threats to one’s safety. I have written about it before, a few times, so I won’t go into it again but today I’m going to mention the third part of this response: freeze.

In nature, animals typically go to flight first, since they are free of ego and have nothing to prove, only to enhance their own chances of survival. If they can’t go to flight and escape danger, they will go to fight, posturing and growling in hopes of scaring off the threat. If this fails, they will actually engage in aggressive behavior, albeit defensive aggression. Once these two options are unsuccessful, or if they are unavailable, most species have a form of reflexive behavior that could be termed “playing dead”.

Playing Dead Emotionally

Since most of the threats people face in our neck of the woods are social or emotional (although many do face actual physical threats in many forms), the freeze response may look a bit different than it does for a possum or cat. In our case, we tend to play dead emotionally.

Playing dead emotionally involves a heightened level of the stress hormones adrenaline and cortisol, both of which serve to numb physical pain in the short term, among other functions. Chronic exposure to emotional stress results in chronic elevation of these hormones, which results in chronic numbing of feelings. The unfortunate wrinkle is that we cannot selectively numb our feelings. If we numb the negative ones, we also run the risk (or certainty) of numbing the positive ones as well.

We may numb our feelings in a variety of ways, including substance use and other addictive forms of behavior such as working too much, eating too much, watching too much TV, and obsessing over hobbies or other people, etc. These activities often provide a welcome distraction and alternative focus for our brains so they don’t have to face the reality of our emotional environment.

Pay No Mind

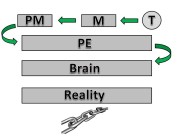

Because the brain wants to be efficient, repetitive behavior tends to develop into reflexive behavior, becoming unconsciously initiate in order to free up precious space in the conscious processing part of the brain. This includes fight, flight, and freeze. We may find ourselves automatically engaging in behavior that fits into one or more of these responses without any forethought or even awareness in the moment.

Why Freeze?

So when do we go to this third option, freeze? Simply put, we do it when we can’t outrun the stressor and we can’t change the stressor. This may include serious and dangerous situations such as chronic sexual, physical, or emotional abuse from a parent, partner, or other authority figure, but it may also include stress from the workplace, health issues, or one’s financial situation.

The Pros and Cons

We can see that the freeze option has its benefits. If it didn’t, then the brain would quickly abandon it. So what are these benefits? The first, as mentioned before, is that it protects us from having to feel pain on a chronic basis, both emotionally and physically. The second benefit is that it buys us time. It allows us to gather our thoughts, formulate a plan and maybe reconsider ways of escape and or fighting back. I will address this latter benefit again but first, let’s look at a serious drawback of the freeze option.

As mentioned before, we cannot selectively numb feelings. If we are constantly needing to numb emotional pain, we will also be sacrificing a certain level of joy. Sometimes the price is worth paying if the pain is great enough. An additional cost of the freeze option is that it actually, like both fight and flight, is only a short-term solution. If we continue to engage in this response for an extended period of time, it actually leaves us more vulnerable than we started. For example, if I numb myself in order to deal with an abusive relationship, I may also rob myself of the opportunity to learn about myself and, importantly, how to spot unhealthy people. This inability to read other people may increase the chances of me being exposed to more unhealthy situations in the future. This is not intended to blame the victim, to say that they brought it on themselves, but it is to say that when we habitually walk with our head down, eyes to the ground, we are running the risk of walking into the lamp post.

One other negative outcome of the freeze response is that while we are protecting ourselves from the pain, we are only doing so on a conscious level. As touched upon in previous posts, much of our information processing goes on far below conscious awareness, in our implicit memories. The freeze response merely expedites this process, shoving the painful experience down below decks. We then may be able to function day-to-day as if nothing bad has happened but all the while, below the surface, the fear and pain associated with the experience continue to fester and leak out. Over time, this can take its toll and it is not uncommon for people who engage in this numbing response to develop autoimmune and anxiety disorders later in life, as detailed by Dr. Gabor Mate in his book, When the Body Says No: The Cost of Hidden Stress.

Why We’re Wired This Way

Having outlined the negative side of the freeze response, one might well ask, if this is such a negative response, then why is it preprogrammed into our DNA? Why would the body have such a system that has such self-destructive outcomes? The answer is quite simple; fight, flight and freeze are all intended for short-term, temporary use. When the bear is chasing you, it’s good to be able to run away. When an attacker approaches you, you may have to fight them off (both physical and emotional attackers). And when neither of these are an option, you may have to go somewhere else mentally until it is over in order to not lose your mind. However, when the bear is gone, you stop running. When the fight is over, you recuperate. When the inescapable pain subsides, we must re-examine our options and find a way out.

Freezing On Purpose

I sometimes encourage my clients to dissociate from their pain in this way. I know that sounds kind of strange, for a therapist to encourage dissociation, but I mean it strictly in a temporary sense. If a client has a terrible job that causes them bountiful stress, we will explore all possible ways to improve the situation. If we have exhausted that angle, it may be necessary for the client to just accept that it is not going to change right now and to stop using valuable energy wishing that things were different. Again, I must emphasize that this is not a long-term solution. It is a way to buy yourself some time. It’s up to you to use that time to recuperate and re-examine so that you may eventually re-engage with the problem, hopefully with a new set of eyes and the energy to make whatever changes are necessary.

I think this way of thinking can be applied to many situations we encounter in life. Instead of fighting against what our brain is trying to do, we must learn to harness it’s instincts and use them to our advantage. If you have any comments or questions, I would love to hear from you.

WoW!! Thank you for this really informative, educational and inspirational piece you wrote!!!!!!! It is really written in such a way that even I could follow and understand it as a layman! It is just scary to understand that I am possibly setting myself up for MORE “bad people” the longer I am stuck in this darkness!!

~ Big thank you from South Africa

I really find your writing very informative and helpful. What do you do if you have been frozen for years?