In 2008, I attended a workshop given by Dr. Gabor Mate. He is a renowned expert in addiction, addiction treatment, and the impact of childhood stress on the developing brain. Needless to say, I learned more than I could write down and ultimately decided to put my pen down and just listen. What I did write down were the names of the books he has written. I then went and bought all four of them and started reading them all at once (hint #1). They were all full of awesome insight and scientific ammunition.

Anyway, one of the books was called “Scattered Minds”, and it was a book about ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder). Since so many of my clients have been (or should have been) diagnosed with ADHD as children, I thought I should learn more about it. What I discovered as I madly devoured this book, was that I displayed almost all of the characteristic signs of ADHD and had done so throughout my life. I realize this is a common experience, even the subject of research, called “psych student syndrome” where people tend to over-identify with lists of signs and symptoms and diagnose themselves with every condition they happen to read about. Thus, I was very careful to ask myself if I was falling prey to the same trap. I read everything I could find, reviewed my school experiences, asked my mom about my childhood, took screening tests on the internet and everything kept coming up the same: There is a strong likelihood that you may have ADHD. Please talk to a medical professional for further assessment.

I began, in my excitement, to preach about ADHD, its origins, its misunderstood nature, its underdiagnosis, its misdiagnosis, the treatment options (of course, I never did finish reading any of those books, they were just too exciting; hint #2). I began to understand myself and to be easier on myself. You see, growing up, I was always a step behind in school. Shortly after this realization, in the midst of my research, my mom found all of my report cards in a file folder with a biohazard sticker on it. In there, I saw what I had heard my whole life: Ted would be a fine student, if he actually sat down, concentrate, talk less, work harder, work faster, be more organized, do his homework, hand his homework in, etc. I mean, EVERY SINGLE REPORT CARD said that same thing for 12 YEARS!!!. It kind of makes you wonder how I went under the ADHD radar for so long. I didn’t have any learning disabilities so there were no red flags; it just looked like laziness to everyone and because that’s what I always heard, I assumed it must be true. Either that or I was stupid and no one had really caught on yet. Neither of those options was particularly flattering to my self-esteem obviously. Nonetheless, this was the idea I had of myself, part-stupid, part-lazy, always confused about why everyone else seemed to know what was going on when I didn’t.

Then came university. I didn’t start until I was 22 and got married in my first semester. I also got a B+ and two A+’s. The A’s were in psychology, which I found fascinating, and I began to realize that maybe I was just lazy, not stupid. I spent the next years proving it to be true as I got straight A’s the rest of the way. However, every time, it was just at the last minute, calculating what I would need on the final exam/paper to get my A. Laziness seemed to be the final answer. For example, I would go to the school on the day of a final exam worth 40% of my final grade with 4 hours to study, fully intending to pour over the books and be really efficient in my methods. I would then spend two hours playing basketball and one hour in the cafeteria, followed by one hour of panicked cramming. The formula seemed to work as I kept getting A’s.

In my former job at a residential addictions treatment centre for men, I was a good counsellor. I connected with the clients, listened to them, chided them as needed and gave them some hope (I think). On the agency side, I was terrible. I hated sitting in meetings (if I even remembered to attend them), I never did paper work (if I even remembered that I was supposed to), I was late with everything, I always forgot to make important phone calls, emails, and was not good at following up with tasks I’d been assigned. All of this doesn’t make for the most professional appearance (neither did my experiment with Wolverine sideburns, but I digress, hint #3).

So when I first read Dr. Mate’s book and recognized myself throughout it, I understood that I made these same mistakes in these same ways for so many years, not because of stupidity or even laziness. I do it because that’s the way my brain is wired. Dr. Mate says that nervous-system-sensitivity is genetically inherited but the environment, particularly the early environment, leads a child to feel safe or unsafe. If the child feels safe most of the time, the development is normal and healthy. If the child feels unsafe, the development is abnormal and unhealthy (it becomes wired to react quickly and impulsively, always unconsciously primed to detect a threat. Think of squirrels. They don’t walk. They don’t gaze. They fly around, herky jerky, no wasted movement, quick reactions, get what they need and get back to the safety of the tree. It’s not because they’re in a hurry. It’s because they’re defenseless and they don’t want to die.

There’s so much research to support this I can’t even begin in this forum to go into it but contact me if you’re interested. Children’s brains are so sensitive to feelings of connectiveness with the caregivers that it doesn’t take much to make a major impact for better and/or for worse.

As I said at the beginning, the realization that I had ADHD began almost eight years ago for me. Since then, my understanding of myself has grown incredibly, as has my understanding of all five of my children, my dad, my siblings, nieces and nephews, a few of my friends and even my grandma. I can forgive myself much quicker for things I used to beat myself up for over and over again. My temper is much improved. I have found some ways to artificially remember things (gotta love smartphones and desktop calendars with alarms). BUT, things were still very tough for me, and often for those who depended on me to come through. I finally decided to follow my own advice and talk to a medical professional about what could be done for me.

From a fellow counselor, I got the name of a local ADHD specialist and got a referral from my family doctor. When I went to the appointment, I laid out my life history. He asked me some unexpected questions and I answered them honestly. He made no indications that he was leaning one way or the other until the end, when he stated, “I believe that you are a very good candidate for treatment”.

He gave me a prescription for Dexedrine, which is an amphetamine psychostimulant. One slow-release capsule and one fast-acting tablet, both to be taken in the morning. This is where things got interesting-er.

He stated that he wanted me to take the medication no later than 6AM. I agreed to do so. Then he said that my brain is made to be up at that time anyway. I was curious what he meant by that. He said that the ADHD brain is the brain of the successful hunter-gatherer. Years ago, the hunter-gatherer had to be alert, reflexive, impulsive, aggressive, high energy, etc. Their brains were wired for that purpose. Then, when people began to live in cities, the hunter-gatherer brain type was forced to sit at a desk for eight hours a day. This is not a good match. He said to me repeatedly, “You have to remember, this is NOT an illness which needs a cure. It is simply the way your brain is made. Medication does not fix anything, it only aids the process. What really needs to happen is a change in lifestyle.”

Early to bed, early to rise, eat right, get exercise, and above all, work at something that requires and engages that hunter-gatherer brain circuitry. I was so excited to hear it described that way. Dr. Mate’s explanation is all about pathology (development of disease) whereas the psychiatrist’s explanation was about health and trying to achieve a good fit between brain-chemistry and lifestyle. I think there is truth in each theory, with each case fitting better for some individuals than the other.

Anyway, I was up most of the night worrying about starting this medication the next day. Would it work? Had I tricked the doctor into telling me what I wanted to hear? Did I want to be sick? Did I want to get better? What would the medication take away from me, for good and bad? Would I still be able to think quickly? Would I be creative, or boring? These questions kept me going from 3:30 in the morning (hint #4) until it was time to take the medicine. I had heard people rave about the immediate difference that the right medication can make and I concluded that even if it only worked because I was telling myself it worked, that would be good enough for me.

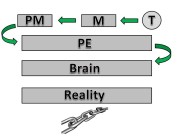

So, just before 6AM, I took my pills. The ADHD brain responds paradoxically to stimulant medication, as in the increase in dopamine in the prefrontal cortex results in increased performance in the executive controls of the brain. I would know pretty soon if I was on the right track. Would I be wired and bouncing around? No. After taking my pills, which was like doing speed, I laid down and went to sleep for half an hour (hint #5). When I woke up, I felt calm, relaxed, and happy. Not like giddy drunk happy, but just really optimistic and balanced. It was going to be a good day. It was a strange thing. Strange and beautiful. I was so excited to change my life.

The biggest immediate change for me was the sense of optimism. I had finally begun to experience my brain as it was capable of working. When ideas came to me, they were no longer automatically followed by a torrent of negative self-talk and pessimism. Because of this, I actually follow through on things I planned to do. I was able to remember tasks and complete them. I was able to greatly reduce my impulsivity and was able to just sit on the couch without having to search for something to occupy my mind. Perhaps the most beneficial outcome of the medication was that I was finally able to organize my thoughts, to formulate a coherent theory of emotional development and how it is injured and can be healed. This understanding led to a revamping of my career and a clarity of purpose like nothing before or since.

Of course, almost immediately after people noticed that the medication was working, they began to pressure me to stop taking it, some in subtle ways, others more directly. Others tried to convince me that it was just the placebo effect or that ADHD wasn’t even a real condition. For someone who grew up plagued by self-doubt, these were not helpful conversations. I persevered, though, and in the eight years since that time, my understanding and confidence in the diagnosis and treatment of ADHD has grown exponentially. I now have the opportunity to share my experience and my knowledge of this condition with people who are where I once was, confused and full of guilt, stumped by the inability to follow through, to learn from mistakes, to stay organized and feel fulfilled by the same stuff as everyone else.

Over those eight years, I have tried several different medications, including Dexedrine, Adderall, Vyvance, Wellbutrin, Cipralex, and Concerta. Each helped in different ways (except for Wellbutrin, which just made me mad for some reason). During this process of education by academics and experience, I have learned that the idea that my ADHD will ever be gone is not based in reality. I am what I am. I have learned to compensate better for my shortcomings, and to recognize my limitations with a bit less defensiveness. Am I all better? No way, but I have also thrown out the idea of “getting better” as it relates to overcoming a sickness. I think of getting better as improving myself. Not cutting out a cancer but learning a skill.

Anyway, those of you who have stuck it through to the end of this note, thanks for caring. If anything you read hit home for you or anyone you know, please follow any of the links, send me a message, or book an appointment.

If this is boring, go do something else.

Incredible insights and vulnerability, Ted. I especially appreciated this passage:

“it just looked like laziness to everyone and because that’s what I always heard, I assumed it must be true. Either that or I was stupid and no one had really caught on yet. Neither of those options was particularly flattering to my self-esteem obviously. Nonetheless, this was the idea I had of myself, part-stupid, part-lazy, always confused about why everyone else seemed to know what was going on when I didn’t.”

It spoke to why I am passionate about being curious, looking beyond what we see on the surface to trying to understand what is happening.

Thank you for writing this Ted. Really looking forward to your posts in the challenge.

[…] My ADHD Story – by Ted Leavitt […]

I so appreciate your willingness to make your inner experiences accessible to others. I went through a very similar evolution to yourself. When I first started medication, I felt the same new found clarity. It was like random pieces of a puzzle finding their way into position without the effort or strain of figuring out where they belong My medication doesn’t always hold me throughout the day depending on a variety of life variables, but I accept my brain much better than I did in the past. At times I resent my limitations because my daughter requires me to keep a fast pace and communicate very difficult processes to others. Writing was a severe weakness for me as it requires organized thinking. If my writing doesn’t fall into place more naturally, I know my brain isn’t supported very well. I’ll reread your post and reflect some more.

Thank you Ted!