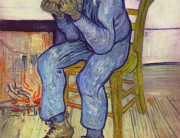

The purpose of this post is to introduce a new way of thinking about problematic behavior. Many of us struggle to curb thoughts or behaviors that are ineffective at best and destructively corrosive at worst. We try and try again, only to meet with failure. Most of us throw our hands up and either set about resigning ourselves to the seemingly inevitable disappointing outcome of our existence, or continue to push against the same brick wall, using the same approach that has already proven so ineffective. This is the cycle of pain.

Kathryn Schulz, journalist and author spoke at a TED conference about the experience of being wrong. She asked participants in the audience to describe how it felt to be wrong. Predictable answers ensued, focusing on the theme of embarrassment or similar emotions. She then pointed out that this was the experience of discovering that you have made a mistake, not the experience of actually making the mistake. She stated that the actual act of being wrong carries with it no emotion of its own; it only carries the emotion and meaning that we give to it.

I would take Schulz’s idea a step further and point out that the meaning that experiences take on is not solely a product of our making but a product of all of the experiences we have been through, directly and vicariously. In other words, for a child, the act of being wrong begins as an emotionless and meaningless stimulus. It is not until mistakes are coupled with consequences and reactions that the child’s brain begins to absorb the meaning of those mistakes, a meaning that is endowed by others, not produced independently.

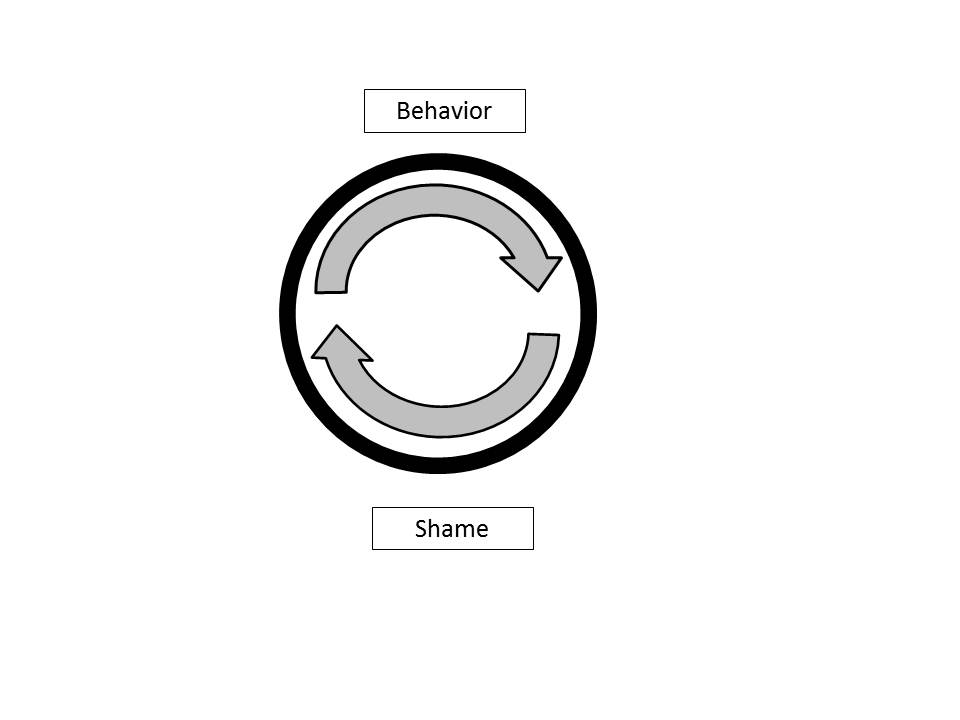

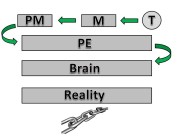

The cycle of pain, as illustrated above, demonstrates that in many cases, the problem behavior or thoughts that we engage in are an attempt to remove feelings of shame, to numb ourselves from pain, to distract ourselves from the present, and to take a counterfeit version of control with regard to our surroundings, both internally and externally. While these behaviors and thoughts may work effectively in the short-term (and they inarguably do, otherwise we would not continue to engage in them), when their effectiveness wears off, we are left with the original shame, discomfort, and pain, often having only exacerbated the original problem.

We then beat ourselves up for thinking or behaving in such a short-sighted way, causing further feelings of shame. At this point, the brain reflexively leads us to the most efficient short-term solution for the feelings, which is often the behavior for which we are currently abusing ourselves. Thus the cycle is a phenomenon that is simultaneously self-perpetuating and soul-cannibalizing.

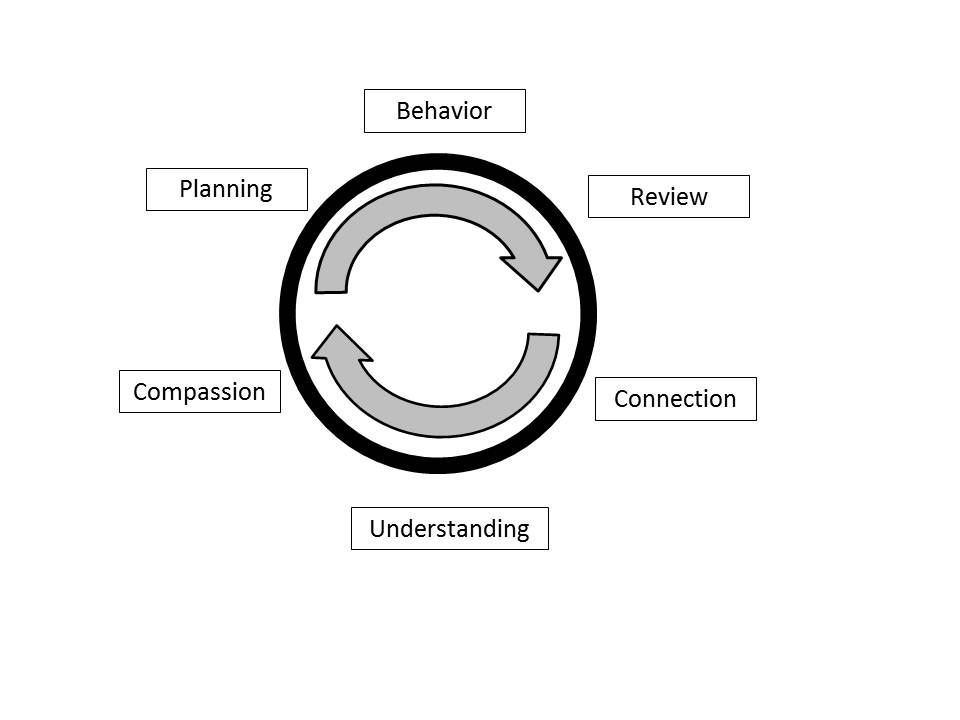

The key part of this cycle where intervention is possible is not before the behavior, though this is the ultimate goal. In the immediate future, the best place to intervene is in the past. By that, I mean that it is crucial that we take the time to review what has happened. By reviewing the situation in great detail, we are able to see the connections that are laced between our recent experience and our more temporally distant experiences.

By taking inventory of the connections between the past and the present and understanding the phenomenon of emotional hallucinations (the brain’s ability to experience fictional emotional events as though they were quite real), we are able to see our behavior and feelings as logical and rational while simultaneously seeing them as ineffective in the long-term.

When we are able to see our behavior and feelings as logical products of previous experiences, we are able to feel a sense of compassion for ourselves, knowing that we are doing the best we can with the limited information that we have. The same process is applicable when attempting to understand the behavior of others as well. This is the cycle of change.

As illustrated above, the final stage of this new cycle is the planning stage. Once we have a more accurate view of what the elements of an experience actually were, we are in a better place to plan for more effective responses next time. Don’t get caught up in the fact that you fall short. We all fall short. Instead, review, connect, understand, have compassion and plan to be more effective the next time.

As I said at the beginning, this is only a brief introduction of these concepts and I plan to write more about this in the future. In the meantime, if you are intrigued by what you have read, agree with it, or think it’s a load of hogwash, please feel free to make a comment, drop me a line, or give me a call.

Recent Comments