“Sometimes when I feel overwhelmed by my stupid life, I get the urge to hurt myself. I take anything sharp that I can find and go to the bathroom. I cut myself on my abdomen, where no one can see it. I don’t even really feel the pain, it just feels kind of numb. If my parents ever found out, they would lose it.”

Self-harm is not a new phenomenon but it is becoming a more prevalent topic of conversation with the help of social media. As with anything, the more exposure it gets, the more armchair psychologists are willing to authoritatively speculate on its causes and what can be done about it. We hear everything from, “they’re just trying to get attention” to “they’re seriously crazy” to “it’s all just an act”. But what is the truth about self-harm? Why, when a person is already hurting, would they want to hurt themselves even further? The answer is actually much simpler than it seems.

If a person is cutting, burning or hitting themselves, it may be a cry for attention, but not if they are doing so in an area that they keep hidden from view. That would defeat the purpose. Since this is the case with most people who engage in self-harm, there must be another explanation.

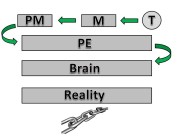

The brain does not distinguish between emotional pain and physical pain. Both are treated as actual threats to actual survival, for that we can think the primitive limbic system, specifically the amygdala. The amygdala is a tiny little structure that exists for the purpose of detecting danger and activating out fight-or-flight response to that danger. It is very eager to do its job but often it’s not very accurate in its assessments. After all, a broken heart is just a metaphor and no one ever actually died from getting dumped.

In a nutshell, when the brain detects pain, it releases an amount of neurotransmitter (brain chemical) called endorphins. The name means “morphine from within”. Endorphins are the brain’s natural painkillers. They are not localized, meaning that if you stub your toe, the brain does not send endorphins to your toe specifically, it just releases them into your pain centre in your brain and the pain is dulled remotely.

Because the brain does not separate emotional pain from physical pain, it responds to them both the same way. Emotional pain can cause the release of endorphins, leading us to feel kind of numb, even when bad things are happening all around us. However, when the stress of life is too great, the brain might not make enough endorphins to keep up with the demand. This is where physical pain becomes useful. A physical injury will lead to the release of endorphins, supplementing the existing supply. In other words, the person who is engaging in self-harm is doing so to release a greater level of endorphins to kill the emotional pain that they cannot handle. It seems paradoxical but it’s true; they’re causing one pain to kill another. In many ways, it is just like a drug. Taking a painkiller temporarily makes life seem manageable but when it wears off, we are left even lower than before. Just like drug use, a person can become dependent on this outside source of endorphins, leading to continued self-harm despite the negative consequences.

Exacerbating this situation is the fact that endorphins are also the chemicals of safe and secure attachment. When a person feels loved and safe, it is because their brain has released endorphins as a consequence of the loving care and attention of a significant person in their life. In our day, when attachments are constantly disrupted and diluted, we have a society-wide epidemic of insecurity. This means that when people feel emotional pain, they are less likely to look to the caring concern of others to soothe the ache, and more likely to settle for the quick fix afforded by substances, activities, and self-harm.

Recent Comments