In the early part of the 20th century, Australian farmers whose livelihood was based upon sugar cane found themselves struggling with a dilemma. Their precious crop was being devoured by beetles. The farmers did not know what to do about the problem until they learned of a species of toad whose tadpoles were poisonous to almost all other creatures. After seeing these toads used to successfully control the pest population in a few other countries, the Australian government decided that it would be a good idea to import just over 100 of these little helpers. They then conducted a study a year later to see if their plan was working and to their delight, they found that it was. The toads, now called Cane Toads, were eating the beetles that had been so bothersome to the farmers.

In the early part of the 20th century, Australian farmers whose livelihood was based upon sugar cane found themselves struggling with a dilemma. Their precious crop was being devoured by beetles. The farmers did not know what to do about the problem until they learned of a species of toad whose tadpoles were poisonous to almost all other creatures. After seeing these toads used to successfully control the pest population in a few other countries, the Australian government decided that it would be a good idea to import just over 100 of these little helpers. They then conducted a study a year later to see if their plan was working and to their delight, they found that it was. The toads, now called Cane Toads, were eating the beetles that had been so bothersome to the farmers.

The farmers were so enthused by the success that they then released approximately 62,000 more Cane Toads to Australia within the next year. This is where things began to get interesting. Not only did the farmers note that the Cane Toads were not very successful in getting rid of the beetles, they also realized that the Cane Toads were having another, unanticipated, impact. One of the appealing features of the Cane Toads at the outset was their insatiable appetite. This led the farmers to believe that the toads would devour the beetles in short order. What actually happened was the toads began to eat everything but the beetles and since they were poisonous and had no natural predators, they went about destroying the ecosystem virtually unchecked. In other words, the Cane Toads became a bigger problem than the original problem.

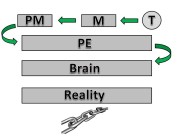

The Cane Toads are a great illustration of how short-term, short-sighted coping behaviour can lead to long-term pain that far outweighs what we were trying to avoid in the first place. For example, raising our voice to get our way may result in being listened to, but at what cost? We have only set ourselves up for future arguments and resistance, instead of being compassionate and persuasive, which will lead to more collaboration. People are often describing themselves and others as someone who “can’t cope”. I disagree with that. All behaviour is a form of coping. It is just a question as to whether the coping has short-term or long-term benefit. Our brains are naturally biased towards the short-term but we have the power within us to override that natural tendency and choose the long-term. I encourage all of us to look at the Cane Toads in our lives and decide what we want to do about them. This is a new year and a new opportunity to be reborn in whatever image we choose.

As we prepare to make those choices, I think that there are few other lessons that can be learned from the Cane Toad situation. First, the farmers saw what they wanted to see. They heard and read that the Cane Toad was successful in a few situations and made their choice based on that information. What they either ignored or were ignorant of, was the fact that the Cane Toads had proven unsuccessful in most other situations. The farmers did not pay heed to those failures, whose occurrence outnumbered the successes. They chose what they wanted, instead of what the full range of experience was telling them.

Second, after experiencing some success with a modest number of toads, the farmers thereafter increased the number of toads exponentially. In other words, they fell victim to the “more is better” philosophy that has caused so much destruction in our world. When this philosophy is applied to our emotions, we end up with hypersensitive, hypervigilant, aggressive, anxious people who can no longer help themselves.

So, when choosing the image that you want to emulate this year, look at all of the data, don’t rush in, and make sure that your solutions aren’t actually problems in disguise.

Recent Comments