Dr. Julie Baumberger, who is awesome!!

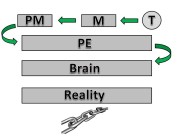

Professor Julie Baumberger, of Capella University, once told me “You are not your brain”. While to many, this statement may at first appear confusing, to me it made perfect sense. The fact that we are able to notice what we are noticing, to think about what we are thinking about (referred to as meta-thinking by hoity-toity academic types) seems to denote some separation between the physical and automatic processes of our lower brain centres and our higher brain centres. Some may take it further and say that it is evidence of the existence of some non-physical part of ourselves, whether it be a synergistic outcome of the firing of neurons or an intangible soul. That is an entirely different discussion and one that will not be tackled here. However, I would like to talk about Dr. Baumberger’s maxim and how we might apply it in a real way to improving our experience of our existence.

First, we need to look at our brain and describe what it is and what its purpose is. If it is separate from me, are we on the same page? Do we want the same things? Do we have the same strategies by which we hope to succeed? In a word, no.

Not sure what flavour this is… Luge Rivalry Flavour?

The purpose and mission of our brain is to survive the moment. This moment. At its most basic level, the brain only considers this moment and not any moment yet to come. As such, it is prone to choosing survival strategies that ensure survival of this moment but may, in fact, sacrifice chances for survival in future moments. For example, consider someone who leaps from a burning building. Are they increasing their chances of long-term survival by leaping from the fourth floor of a burning hotel? No, but they are ensuring that that they at least survive that particular moment.

We do the same thing on a daily basis, although usually on a much less dramatic stage. Consider a person who overeats. The neurochemical payoff of ingesting large quantities of carbohydrates and fat (similar to the high of an opiate user) allows the person’s brain to feel the relief they crave, but only for that moment. In the long run, they decrease their chances for relief because of the body’s tendency to develop tolerance to pleasure-seeking behavior and because of the health problems that overeating may lead to. In a sense, wolfing down that bag of Doritos may be closer to jumping from the burning building than we realize.

Another thing to realize about our brains is that they are very easily tricked. They are earnest. They want to do the best thing for us. They want to protect us. They want us to feel good. Because of this programming, our brains try to make things as automatic as possible. My brain doesn’t want me to have to worry about the minutiae of my existence, just to focus on the big picture. It collects data from my experiences, files it away in collections of other similar data, and refers to it when it believes it is necessary.

Mommy?

This metaphor is easier to visualize if we use an example. Consider a child who is learning to talk. Let’s say the child’s first ‘word’ is “ba”. Everything is ba. Trees are ba, dogs are ba, mommy is ba, TV is ba, food is ba, etc. Through teaching and modeling, the child learns that “ball” is ball and “mommy” is mommy. However, the child’s brain, in the beginning, may be under the impression that everything that is round is a ball and that all females are mommy. I remember my son referring to the peas on his plate as balls and attempting to bounce them. Through teaching and modeling, the child learns further categories for labels until he has a fully functioning vocabulary.

A similar learning progression happens with our emotions. In the beginning, everything is a threat to the infant’s survival. Eventually, as the child gains experience, it is better able to differentiate between real and imagined threats. The child learns that they won’t die if they are hungry or warm or tired or if they don’t get their peanut butter toast RIGHT NOW!!!

Despite the brain’s efficient system of learning, it has it’s drawbacks. One of the chiefest amongst these is the reality that much of this learning and association is taking place deep below the surface, far beyond our consciousness. Because our brain is geared towards survival of the moment and making our mental and physical processes as automatic as possible, it doesn’t share these processes with us on a conscious level.

In essence, it tells us “Don’t you worry about it. I’ve got it under control. I’ll protect you in the future”. When it comes to perceived threats, its idea of protecting us is to engage our fight or flight system whenever it’s simplistic worldview feels that we are in danger. It thinks that it is doing you a favour, that it is protecting you. According to its experience, that’s exactly what is happening.

Don’t worry, I’ll protect you from the blogger!!

You can apply these same principles, which have been admittedly watered down in this discussion, to any thought, feeling, or behavior process that seems to occur automatically. So, if your brain is causing your thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, and is doing so out of a desire to protect you, why does it seem to lead us into harm’s way so often? That is the question that many ask and that we will attempt to answer in part II and III.

Recent Comments